“Let me tell you some things I find productive. Positive reinforcement. Negative reinforcement. Honesty. I’ll tell you some things I find unproductive: constantly worrying about where you stand based on inscrutable social clues, and then inevitably re-framing it all in a reassuring way so that you can get to sleep at night. No, I do not believe in that, at all. If I invited you to lunch, I think you’re a winner; if I didn’t, I don’t. But I just met you all. Life is long, opinions change. Winners, prove me right. Losers, prove me wrong.”

— Bob Kazamakis

Founded in 1944 as the “Winnipeg Sales and Ad Club”, the Advertising Association of Winnipeg (or AAW) has for many years – and rightfully so – laid claim to being “Manitoba’s largest advertising, marketing and graphic design community”. The organisation recently hosted its 2023 Signature Awards, an annual industry shindig meant to honour and celebrate the very best work of its membership. That each year’s winners indeed represent the “best of the best” work being done, we can be certain, for the event’s homepage assures us that “the Signature Awards entries are judged by an unbiased international panel of senior-working industry professionals”.

The AAW’s 2023 call for entries… erm, called for entries in the categories of “best individual online ad”, “best collection of online ads” (these first two being judged on their overtly ‘creative’ aspects), “best website”, “best microsite”, and “best social media campaign” (these last two would be folded into the “Miscellaneous” category by the time finalists were announced). You will note the absence from that list – as from every call for entries which has preceded it – of any category of honours, recognised by the largest professional society to which I might belong locally, under which any aspect of my own career might sensibly fit.

All the same, for curiosity’s sake I recently decided to run some checks and audits on the winner of this year’s Signature Award in the “Best Website” category. The winning agency’s client is (or was) a charming little bed-and-breakfast in rural southwestern Manitoba. I’ll refrain from naming either party here, so as to save them any undue embarrassment:

- A basic Lighthouse audit gave the AAW’s “Best Website” of 2023 a performance score of 39 out of 100 on mobile devices– that is, firmly entrenched in the bottom half of all known websites (according to the HTTP Archive) when rendered in that context.

- Whatdoesmysitecost.com suggests that the data-transfer involved in loading the homepage of the AAW’s “Best Website” of 2023, via a mobile network provider, would cost a typical user more than $1 USD.

- A “Carbon Control” report generated via WebPageTest.org estimated that each new visit to the AAW’s “Best Website” of 2023 emits roughly two grams of CO2 into the Earth’s atmosphere. That’s more than three times the average estimated emissions per visit to any of the top 1000 sites on the Web.

- The AAW’s “Best Website of 2023” doesn’t have a privacy policy, which is a de facto breach of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). The website and its owners have failed to satisfy the barest of bare minimums of consumer data protection as have been required under Canadian federal law for the past quarter-century.

I don’t wish to give the impression that my intent is to go on “punching down” at my chosen example here – that would be unfair. But it would be similarly unfair of me, or anyone else, to suggest that the sorts of criticisms one could level, on the basis of the points I’ve just made, would be in any way especial. That isn’t the case. Having now audited all of the 2023 Signature Award finalists, judged in either the “Best Website” or “Best Microsite” category, I can tell you that these Best Website winners were not even the only member of the shortlist with glaringly obvious legal violations. In that other instance, in the spot down in the website’s footer where one might normally find the links to privacy disclosures mandated by PIPEDA, one could instead find this brief note of gratitude: “Funded by: Justice Department Canada”.

There’s Something on the Wing of the Plane!

Perhaps the main benefit of what headhunters will refer to as my “diverse working experience” (obvious code for “routinely unemployed”) is that I’ve managed to get a number of “inside looks”, on both the buy-side and the sell-side of advertising, at how professional marketers operate in all sorts of contexts and environments. Here is normally where I would pile on with the appeals to authority, but let’s skip all of that and just say that I’ve worked with all sorts. So I’ll spare you the aggravation: it’s turtles, all the way down.

As a rule, “digital marketers” are not good at digital marketing. That much is obvious. What I mean is that the prevailing majority of people employed today as “digital marketers” – in varying capacities, and of varying stripes – could not tell you accurately, and in terms you might understand, what it is that they do, or what they are trying to do, or even what it is they’re meant to be doing (for in practice, the honest answers to these questions would often be distinct). This too is obvious – or at least, I contend, it should be. It is my carefully considered professional opinion as a digital marketer, and you may cite it for all that is worth.

Supposing that we can agree on this point, you might still feel that what I’m describing is a phenomena concentrated mainly towards the lower ends of the pay scales; surely, the real money people have their heads screwed on tight! Earlier in my career, I harboured a similar suspicion that my own experience of a vast and growing “competence chasm” in my chosen field could largely be chalked up to, let’s call them, “local factors”. Again, it just isn’t so. In a post-pandemic economy, geography is no longer the barrier it was to working with (and for) larger companies and brands, with the big offices in the big cities. So I can tell you with moderate confidence that the kind of pervasive, deep-rooted, and systemic ignorance that I’ve described is by this point endemic at virtually every level of marketing campaign management. What else can I say? It is what it is, and we are where we are.

This can all get to being – to put things mildly – a bit of a problem, especially when contemplated on the scale of a company, or an industry, or of the entire digital economy writ large. Indeed, as someone whose day-to-day work often revolves around fixing the assorted problems that arise from this more fundamental one, I often find myself at a loss in tying to accurately convey its bigness (though I will be making another attempt, in the following post).

For a few years, I had come to rely on a particular favoured metaphor to explain one such “big problem” that many digital advertisers face: namely “conversion attribution”, which is just marketer-speak for “who gets credit for what?”. It first came to me back in 2021, when Apple began enforcing their “App Tracking Transparency” framework with the rollout of iOS 14.5. Suddenly, digital publishers were being required to seek express consent, from most iPhone users globally, to their invasive user-tracking and data-harvesting practices. And almost just as suddenly, many discovered that most users (gasp!) would prefer not to.

I won’t relay the entire thing for you here, but it involves a commercial airliner taking off from one airport, headed for another several hours away, when a natural disaster causes sudden catastrophic damage to all the runways at their destination. Various marketing stakeholders stood in for the roles of the flight crew, passengers, air traffic controllers, and so on. In hindsight, it is perhaps telling that this was the simplest metaphor I had arrived at yet, even with non-technical audiences in mind.

But the point of my imagined scenario was this: we can no longer follow our earlier plans, because real-world conditions have irrevocably changed. Nevertheless, the aircraft must and will still land. It has a finite supply of fuel, which constrains its remaining flight-time, and thus the places that might be reached to attempt a safe landing. The overwhelming majority of “alternative landing sites” are manifestly unsafe, and risk catastrophic losses to both aircraft and life. Of those scarce few locations which are safe to attempt a landing – other nearby airfields, for instance – some will be preferable to others.

In short, the situation is dynamic, and time is ticking. So: what should everybody do next?

Beer Ain’t Drinkin’

More recently, I have encountered – and tried to integrate into my work– a number of concepts from “systems thinking” in general, and “statistical process control” in particular. Among these most recent projects, I can say with total frankness, is some of the finest work of my career. My employer, and their clientele, seems pleased as well. But before any of that could happen – and indeed before it can keep happening, as a going concern – another new (yet by now familiar) conversation must always be had.

At the outset of each new project, a new group of people (the “stakeholders” I mentioned earlier) must come to a consensus about what their problems are, and how they intend to go about fixing them, before they can commit, collectively, to having a(nother) go at it. One becomes acutely aware of this process when advocating for a specific approach (say, statistical process control), within a novel context (say, digital marketing management), wherein many of the stakeholders can be relied upon to see many of its conclusions as falling somewhere between “counterintuitive” and “career-ending” (at least, at first blush).

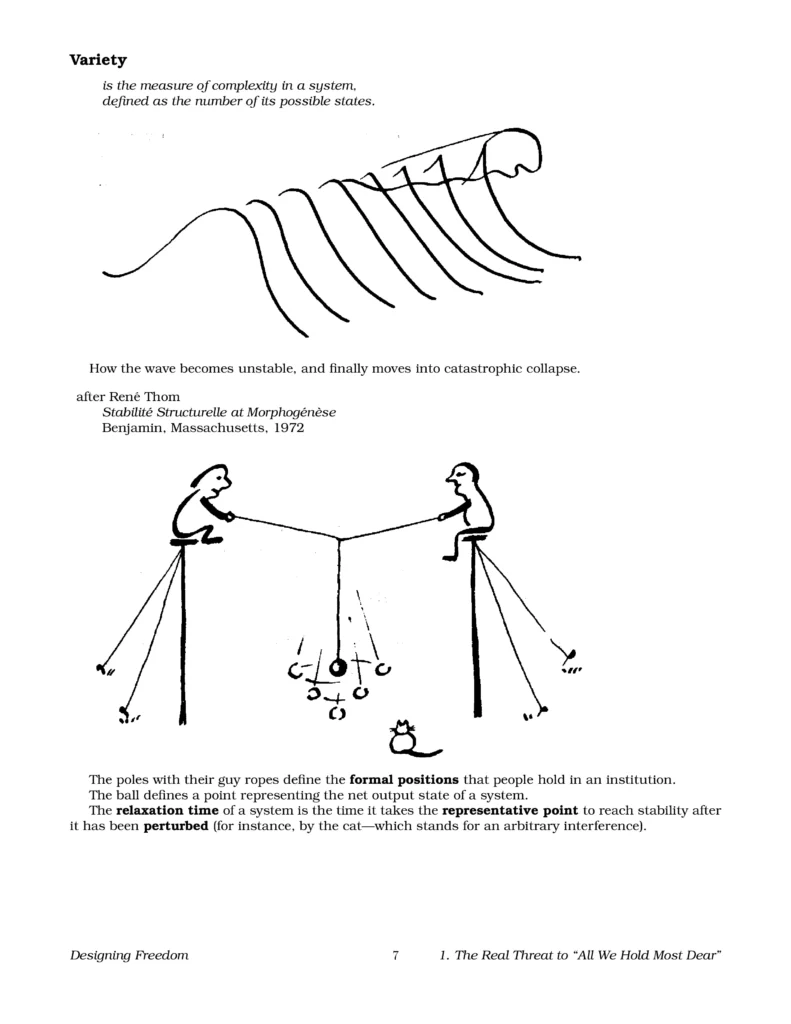

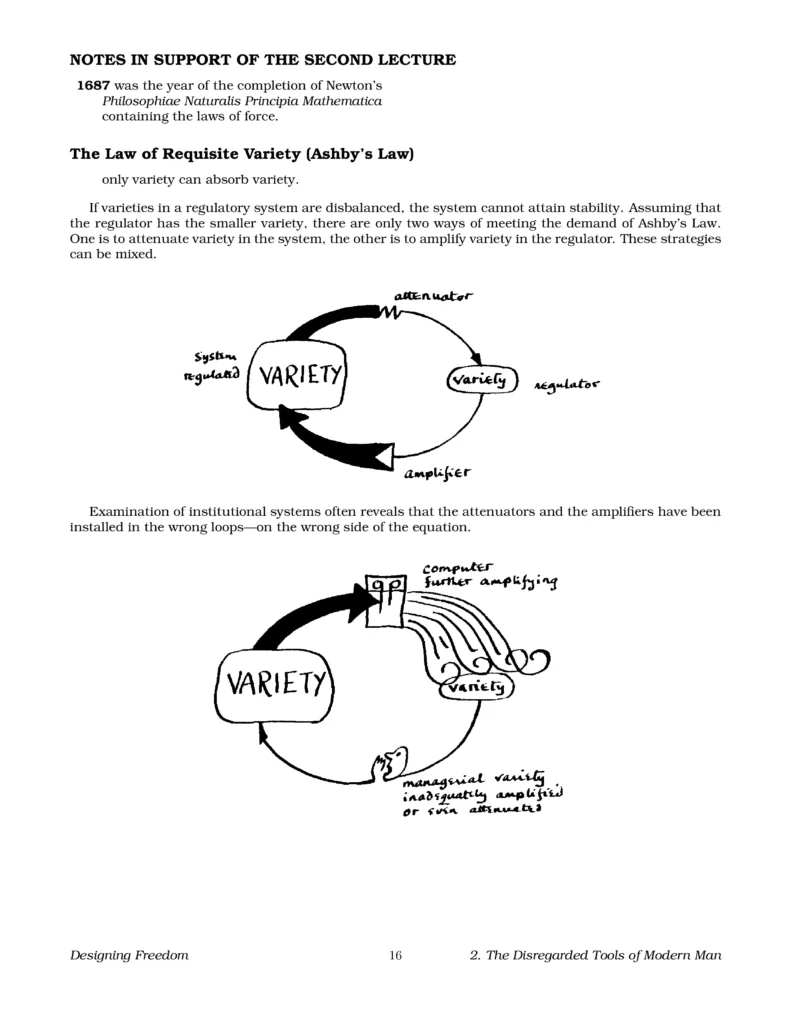

Imagine my happy surprise, then, in having recently stumbled across the work of British cybernetician Stafford Beer, and in particular, his 1973 treatise Designing Freedom. A brisk fifty pages, many of which are given over to the author’s own hand-drawn notes, Designing Freedom was first presented as a six-part series of half-hour radio broadcasts. These were the 1973 Massey Lectures, commissioned and published by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, in which Beer attempts a popular introduction to cybernetics (or in his words: “the science of effective organisation”).

I shall call this “my happy surprise”, for that is the kind thing to say. There is also, I will freely admit, a keen and searing sense of intellectual jealousy in finding such a superior distillation of so many concepts that I have struggled and meandered my way towards articulating, over many years and using various sources, all presented in one text, in such clear and suasive terms.

Here, let me show you what I mean. It’ll be good for me, probably.

How It Started

A year or two ago, I was invited to give a lecture on (what else?) digital advertising, to a class of students in the “Advertising” stream of the Red River College Polytechnic’s “Creative Communications” program. This was, to me, a very exciting prospect – how often do we “working people” have an opportunity to speak directly with those now aspiring to enter our same profession, and to tell them (a bit of) what (we think) it is they’re really getting themselves into? I doubt that I’ll be invited to give another.

Not that there was any trouble “on the day”, mind you, for my talk seemed to be well-received – at least, as far as you can tell these things through a video-call. I had a fine time, and very much enjoyed the experience. No, my doubt stems from having neglected to send back some paperwork related to a $50 honourarium. The forms had asked for my Social Insurance Number, and I felt this was a bit much for fifty bucks, and this surely caused some annoyance to the instructor who had been kind enough to invite me, and also to the College’s Accounts Payable department. Anyways.

This being a rather expansive subject – and me being the sort of person I am – I eagerly set about slapping up the dozen-or-so slides that I felt I would need, and combing through the “prior art” to help tie concepts back to real-world examples. And so, on the day of my presentation – after some perfunctory definitions of “AdOps”, and of some key bits of industry jargon, and rattling off a few of the most common tasks and responsibilities in this line of work – I arrived at the thesis of my talk. And this time, I will relay it to you in full:

- Digital advertisers work within, and are tasked with administering, systems of enormous complexity. One need not go on at length, recounting all the terrible and wondrous things that online advertisers can do (or claim to do) to appreciate that these depend upon numerous, complex, interconnected systems and sub-systems.

- Operating within (and upon) these complex systems, digital marketers are usually tasked with performing good work on behalf of other stakeholders, and with communicating the results of these efforts to those stakeholders. This is a key detail, since – with rare exception – the essential function and goals of “marketing” are subordinated to those of the larger institution. To put a finer point on it, very few organisations or brands exist for the “animating purpose” of communicating this existence to the world. Something more is often required.

- It is therefore useful to consider how people – and by extension, organisations – actually go about “knowing” things. And it is here that I submit that one will find three strategies are prevalent within the discipline of professional marketing today:

- Inspection: Careful examination and analysis of one’s work-product, subjecting this to (at times destructive) testing. This method is analogous to, and to great extent modeled after, the ‘intuitive’ ways that children and other animals have been observed to go about learning about the world around them.

- Pros of Inspection: Capable of identifying perceived errors, defects, or strengths in a given process and/or its outputs

- Cons of Inspection: Labourious; cost in both time and resources, typically occurs “after the fact” (i.e. “post hoc analysis”)

- Fraud: Fabricating aspects of one’s work, in order to satisfy (in the immediate and surface sense) the needs and expectations of external stakeholders. This is, I must stress, the most prevalent strategy one encounters in professional practice today.

- Pros of Committing Fraud: It is often less difficult (in some contexts, trivially so) to produce correct-sounding responses to informational requests. External “stakeholders” will often lack the domain knowledge and/or resources necessary to challenge answers which deviate from reality

- Cons of Committing Fraud: Moral hazard; reputational risk; it tends not to feel very good

- I try not to belabour the point, since most folks don’t need “fraud bad” explained to them. People know it’s bad. Nevertheless, fraud is inarguably a strategy, and so it is useful for us to contemplate the circumstances in which a person, or group, might choose to adopt it

- Statistical Process Control (SPC): This approach was the subject of the remainder of my lecture. In the words of one of the field’s pioneering minds, W. Edwards Deming, “the statistical control of quality is the broadest term possible for the problems of economic production“.

- Pros of Statistical Process Control: Near-real-time monitoring of the “outputs” of a given process; an emphasis on early identification and prevention of faults in a process, rather than reliance on “post hoc” review and/or analysis to understand, and iterate upon, the end-results

- Cons of Statistical Process Control: Less intuitive than either of the two preceding strategies; some degree of re-training and education is often required of all project stakeholders in order for such methods to prove successful and effective

- Inspection: Careful examination and analysis of one’s work-product, subjecting this to (at times destructive) testing. This method is analogous to, and to great extent modeled after, the ‘intuitive’ ways that children and other animals have been observed to go about learning about the world around them.

From there, I went on to describe the concept of “variation”, and “normal distributions”, and Shewhart’s invention of the “control chart“, and the need to distinguish between the “stability” of a process and its “capability”. Since then, I have also added a section that addresses “process tampering” (AKA “overcontrol”), and another one on the basic natures of “quality” and of “loss”. Those more recent versions have come to form an hour-long “crash course” of sorts, which I’ve made a habit of offering (some might say “threatening”) to deliver to most professional colleagues, at some point or another. Trust me, if we work together for long enough, it will come up.

How It’s Going

Did you manage to follow along with all of that? If you did, then great, I’m so pleased! And if you didn’t, then that’s fine too – you wouldn’t be the first, and the fault is likely mine. But now, here, let me share just four pages from Stafford Beer’s lecture notes in the published version of Designing Freedom. Know a little better my seething brain-envy.

If the doodles below intrigue you at all, but there is another part of you shouting that yes, this is all fascinating, no really, but that you’re just not feeling up for three-or-so hours of heady, far-ranging lectures on foundational cybernetics from fifty years ago, then that is perfectly fair. We’ll stop here, for now. But if that does happen to be the case for you, then might I suggest saving this one for a summertime beach-read (or listen)?

No, really – here are just the first three sentences, from the first lecture:

The little house where I have come to live alone for a few weeks sits on the edge of a steep hill in a quiet village on the western coast of Chile. Huge majestic waves roll into the bay and crash magnificently over the rocks, sparkling white against the green sea under a winter sun. It is for me a time of peace, a time to clear the head, a time to treasure.

In Part II (coming soon!), I plan to return to those “big problems” I was talking about before, while relaying some of the ideas presented in the first three lectures from Designing Freedom. In Part III, I hope to focus on Stafford Beer’s fourth lecture, which introduces the concept of an “electronic mafia”, and try to sort out why it strikes me as a more apt metaphor than some more recent (and fashionable) framings like “surveillance capitalism” or “the enshitternet“.

Happy New Year,

– R.